Issue 159,

Chroniclers of the Crusades

The last issue of 2023 brings us more interesting medieval chronicles – this time from the Crusades, as we focus on the stories from those who relayed contemporary accounts of the battles, motivations, and the key characters who accompanied crusading armies over the course of several hundred years.

We begin with Oderic Vitalis – our earliest crusade chronicler in this issue – and his take on the events of the First Crusade and the history of the Latin East. His Ecclesiastical History (1142) provides us with an interesting glimpse into the impact of the crusading movement on Norman society and also addresses why the crusades mattered to people at that time. We move onto our next chronicler, or chroniclers I should say – two authors who demonstrate that crusade narratives could differ wildly and that we should always remain alert to bias. They both recount the events of the Albigensian Crusade and the actions of its leader, Simon de Monfort (1175–1218). The first of these, Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay (†1218), was a staunch supporter of Simon; the second, the anonymous author of the Song of the Cathar Wars, was incredibly critical of Simon and took immense pleasure in his grisly demise. Then we move on to two of the most famous chroniclers of the crusades – Geoffrey of Villehardouin (1150–1213) and Robert de Clari (1170–1216) – and how their writing sheds light on the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath.

Happy Holidays to you and your loved ones 🎁 ❄️

IMPORTANT: Please note this is a DIGITAL magazine and is not delivered in print format. You will receive a unique link where you can download your purchase to read on any device.

Articles

Earning Your Badge

Mementos of

Pilgrimage

By Danièle Cybulskie

One of the brilliant things about humankind is our desire to continuously strive to accomplish difficult things: epic journeys, great feats, tough challenges. We do this to learn more about ourselves, to test ourselves, or sometimes to set ourselves on a spiritual journey. One of our most enduring and common impulses is to share our triumphs with the world. While the majority of people who climb Everest today doubtless do it for personal reasons, rare indeed is the person who climbs the mountain and never tells anyone.

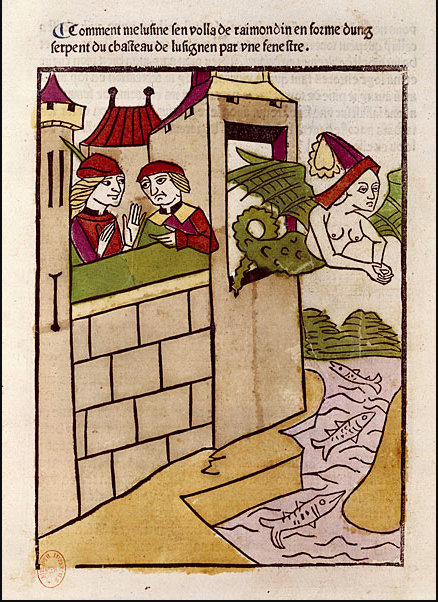

Melusine: History’s Queen Maker

By Christine Morgan

Considering the fairly recent pop-culture shift toward a fascination with genealogy and family ancestry, it should hardly come as a surprise to lovers of history that the present wave is perfectly indicative of a historical pattern—as most things are. The myth of medieval matriarch, Melusine reads as the world’s most fascinating episode of “Who Do You Think You Are?” and blurs the lines of reality and mythology so expertly, that the medieval period gave way to entirely new family dynasties. Not only is the epic poem significant in the role of establishing territorial power, “blood” politics, and the right to rule, but Melusine also lends her magical superpowers to history in a way that elevates and validates women as rulers. Melusine’s “mermaid queen” image even appears on your daily cup of coffee, arguably another type of magical superpower—but that’s a different conversation.

Mirror of an empire

Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel

By Jo’anne van Ooijen

The ‘Carolingian Renaissance’ of the late eighth and ninth century brought about a revival in education, literature, arts, architecture, and legal studies. It has often been interpreted as an attempt to revive the spirit of the Roman empire, but there was more to it than that. The world had changed drastically since Roman times. Charlemagne’s reign covered many regions and peoples across the vast territory that was united under his rule, but lacked cultural cohesion. The Palatine Chapel in Aachen is the most important architectural testimony of the Carolingian era. It combines different architectural influences that together mirror the multifaceted Carolingian world.

Korea’s Sixteenth Century Muse: Introducing Hwang Jini

By James Blake Wiener

A revered cultural icon and national muse for nearly five hundred years, the infamous Korean courtesan Hwang Jini (c.1500–1560s) has been the subject of novels, widely acclaimed television dramas, an opera, and several films. While renowned for her beauty, prodigal intellect, and exquisite dances across the centuries, only a few fragments from the past allow us to reconstruct the talent and the brilliance of a fêted polymath. Modern Koreans remain captivated by the elusive, but compelling, Hwang Jini because of her individuality and the romantic intricacy of her poetry.

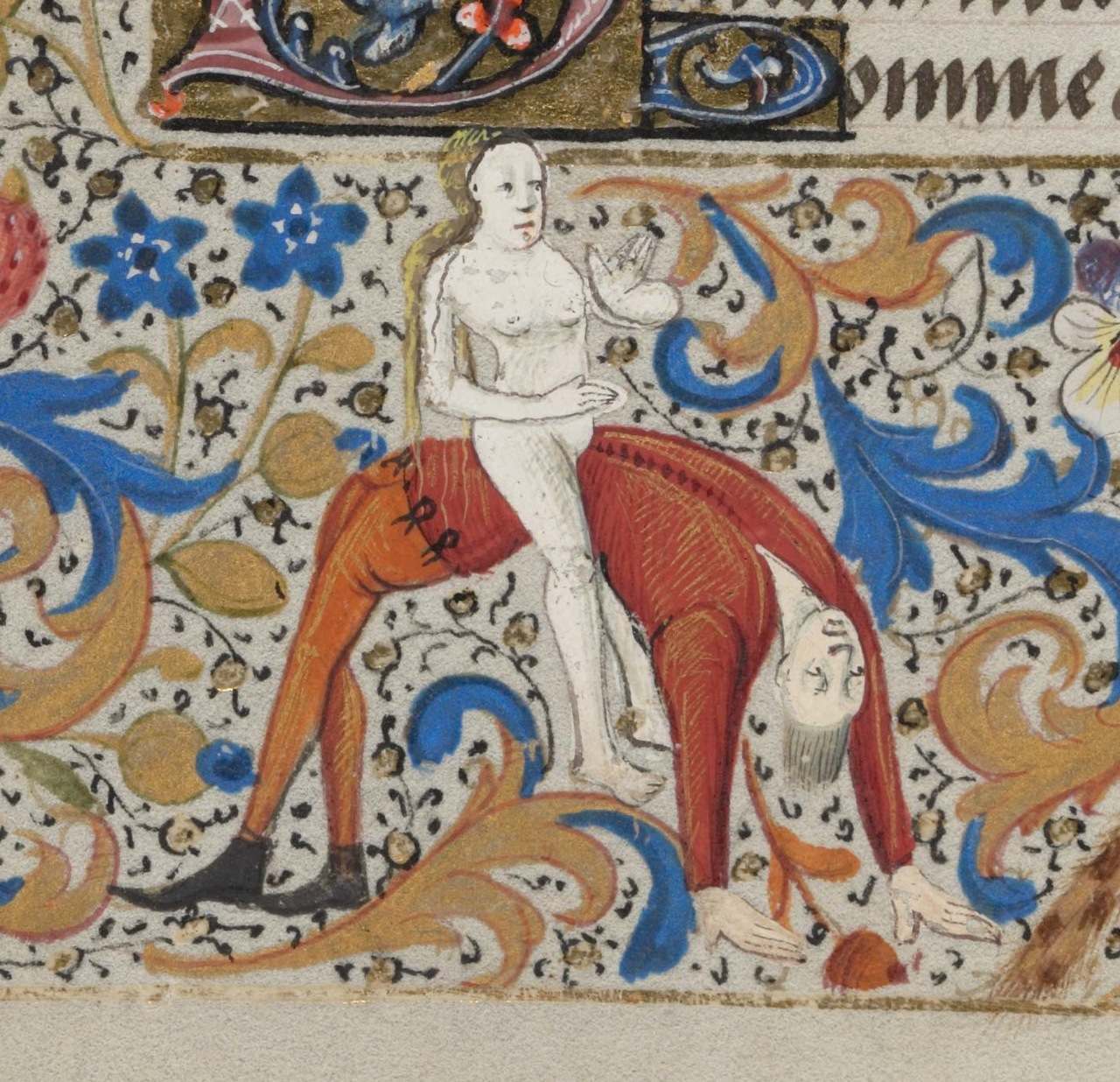

“A Guide to Medieval Marital Sex”

By Lucie Laumonier

Attitudes towards sexuality in the Middle Ages were largely shaped by the Church. Only permissible when between spouses, sexuality was solely aimed at reproduction. Medieval canonists and theologians commented abundantly on sexuality. The austere views of the Church on sexuality contrasted with medieval literature, in which authors depicted a more joyful and spontaneous image of sexuality. Yet, what historians know about medieval sex draws in a large part from the Church’s normative frames, and from sources pertaining to their enforcement through trials and disputes in the courts of justice. The Church’s views on sexuality were not set in stone but changed through time; sexuality became more of a direct concern for the reformists of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, who defined broad guidelines for the laity to follow.

The Cult Of Saints: Sainte Foy

By Sydney K. Gobin

Divine rays of ethereal light stream through rich, multicolored glass; overwhelming scents are emitted from hanging lanterns, masking the indistinguishable mixture of odors brought into the sacred space; footsteps echo against the cavernous stone walls. Angels, demons, saints, and prophets peer downward imploring self-reflection and fear upon the visitors; recalling those they left behind and those who came before. Monopolizing the senses, the pilgrimage church served as an awe-inspiring symbol of the holy power which reigned supreme in France during the Middle Ages. These monumental stone institutions were part of a network of churches leading the penitent pilgrim along their treacherous journey of hope.